Vestal Virgins: Feminism & Burial Alive

Despite the richness of the Vesta tradition, many people who think Vestal Virgin still think of one thing: the fact that ancient Vestals who broke their vow of chaste service to the goddess were buried alive. Let’s be honest. Who can blame people for going there? It’s a pretty dramatic image: a young woman being thrown into a shallow grave and trying to claw her way out while dirt is being piled on top of her.

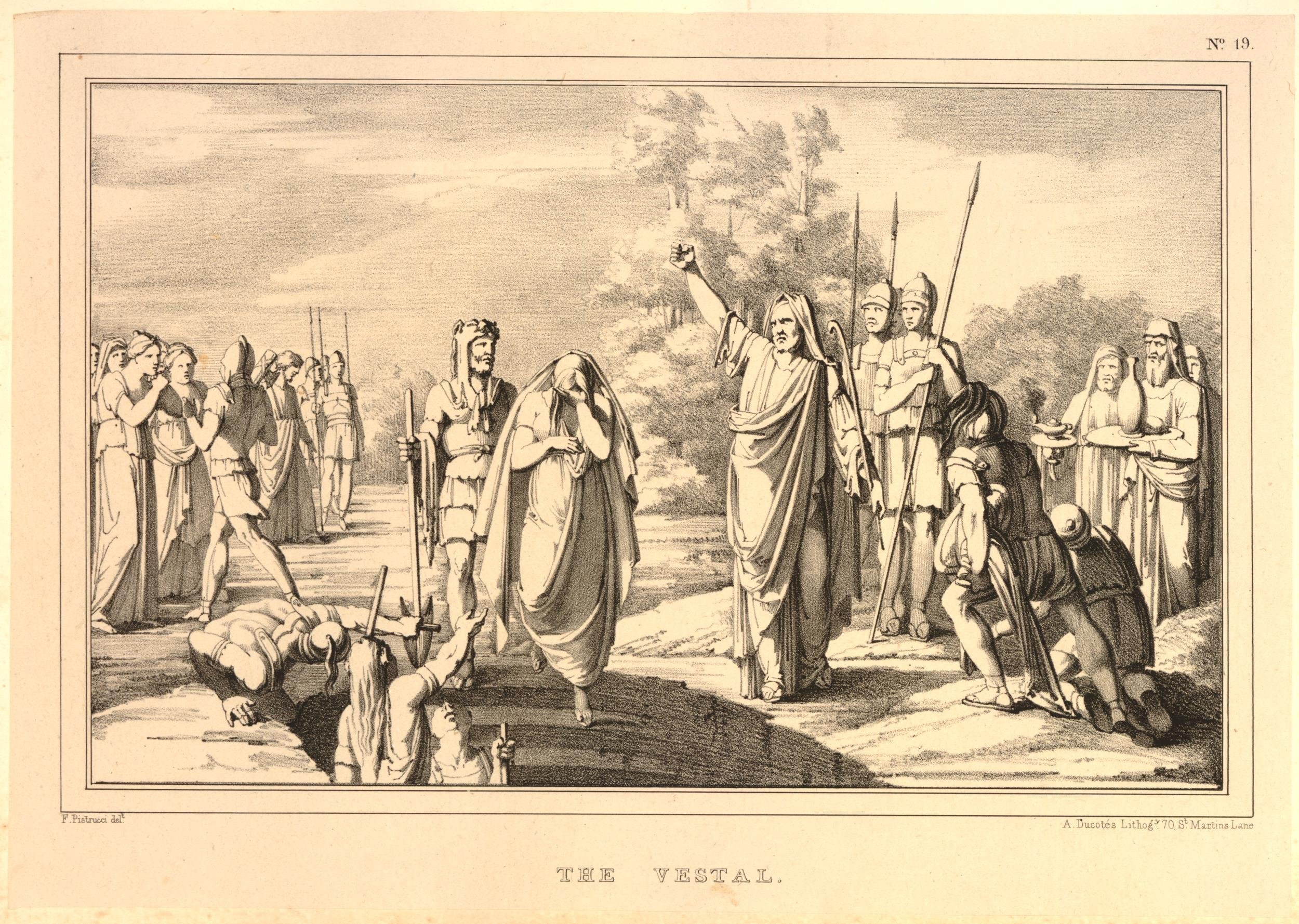

The Vestal. British Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Of course, that isn’t how it happened. It was considered a sacrilege to kill a Vestal, so those who were found guilty of incestum (breaking their vow of chastity) were taken to the Campus Sceleratus or “evil field” just inside the city walls of Rome where they descended a ladder into a subterranean pit. They were given enough food, water and light to last a few days.

This way of punishing a Vestal – bringing about her death without actually killing her – absolved the Roman people of guilt for the priestess’s death. Yes, it was a technicality; however, the ancient Romans were known for that kind of thing. Another misconception is that being buried alive was a common occurrence. Not so. In the thousand-plus years that the Temple of Vesta was active in the Roman Forum, only a handful of Vestals were ever killed in this way.

Finally, some people automatically assume this punishment — along with the vow of chastity itself — was a misogynistic way to control female sexuality. Such an assumption is perhaps a lazy way to look at history: it looks through a 21st century lens, which often includes a hypersensitivity toward gender issues and fails to truly put these things into historical, social or religious context.

Vesta, goddess of the home and hearth, is symbolized by and resides in her sacred fire. In antiquity, her fire burned in Roman homes as well as in the inner sanctum of her temple in the Roman Forum and other cities throughout the empire. The ancient Romans believed that Vesta’s fire protected their world, families and lives, and that if the fire went out, Rome would fall to invading barbarian armies. Their men would be slaughtered, their women and children violated and enslaved, and their entire way of life destroyed.

To prevent this from happening, an order of Vestal priestesses was created to keep the eternal flame alight in Vesta’s temple. The Vestal order was Rome’s only full-time, state-funded priesthood. By guarding the flame, the Vestals ensured the pax deorum – the peaceful contract between the gods and humankind – would remain unbroken.

Choosing suitable priestesses for this duty was essential. After all, the more Vesta approved of them, the more likely it was that she would continue to protect Rome and her people. Because Vesta is a virgin goddess and fire is a purifying element, young girls were selected as priestesses and took a thirty-year vow of chaste service to the goddess. It was believed this state of purity was necessary to perform Vesta’s rites. It also granted priestesses special status to petition Vesta to protect Rome, particularly during times of crisis. Their virginity was therefore not necessarily an attempt to control their lives, but rather a consequence of the circumstances required to perform their duties and remain in the virgin goddess’s favor.

Nor did the years of sacrifice that a Vestal made go unnoticed or unrewarded. (Although considering the limited rights and choices most women had at this time, being a Vestal may have been more of a blessing than a sacrifice.) Vestals lived a life of luxury, privilege and relative independence. They were influential in the political sphere and were venerated by society at large. And, after their thirty years of service, they were free to leave the order as wealthy women who were still young enough to marry and perhaps even have children. Some did choose to marry – as rich, well-connected women they were certainly desirable wives – but many chose to stay with the order.

But back to the punishment of being buried alive. Was it motivated by misogyny? I don’t think so. Rather, I think it was a punishment that the ancients believed fit the crime, even though the crime is one that to our 21st century sensibilities isn’t a crime at all. It’s also worth noting that a Vestal’s male lover didn’t fare any better than she did. He would be flogged and publicly executed.

Of course, an assigned life of chastity – even one that came with some big perks – isn’t something we’d support today. Indeed, there is evidence that the Vestal order itself was challenging this as early as the 1st century CE. Moreover, the emperors of the early empire granted “Vestal privileges” to female family members, thus freeing them from the patria potestas. In this way, Vestal privileges were an early form of women’s rights that could be expanded beyond the Vestal order. Was this fledgling feminism? I think so.

But like any social change, this one was destined to move forward in stops and starts – and its biggest stop was the violence and oppression committed against the Vestal order not by the polytheistic establishment, but by the first Christian emperors whose androcentric and monotheistic religion demanded the total destruction of a socio-religious order that elevated the status of women.

This article is by no means an exhaustive look at the Vestal order. It would take volumes to cover this issue in a comprehensive way. My goal here is merely to make us re-think the knee-jerk assumptions we make when we look at Vestal practices and punishments. I have long believed the Vestal order was an early vehicle for feminism and were it not for the intolerance and agenda of early Christians who found themselves in positions of power, I suspect it would have expanded its influence and relevance to advance the status of women in the ancient world. This would have happened slowly and imperfectly, but I suspect not as slowly and imperfectly as it did (or has yet to do) in a world dominated by aggressive androcentric monotheism.

After all, the Vestal order and its priestesses had the emperor’s ear, influence in the Senate, and moved in important circles. Had they been given more time, perhaps they could have made changes from within, changes that would have spread throughout the empire to improve the status of women in the larger world.